Commerce City activists and residents continue the fight for clean air

Suncor Refinery fined $10.5 million after releasing toxic chemicals; is it enough?

Less than a year after moving to Commerce City, Colorado, Helen Geda is experiencing asthma symptoms unlike ever before.

“I'll have the window cracked for, like, 30 minutes. And I'll be sick for like two weeks,” Geda said.

Helen Geda poses for a photo at her Commerce City apartment on Feb. 25, 2024

Helen Geda poses for a photo at her Commerce City apartment on Feb. 25, 2024

Geda grew up in the suburbs of Thornton, Colorado, a town outside Denver. At the age of six, she was diagnosed with asthma. She lived with her parents and her younger sister until graduating high school. Since then, she has lived in North Denver, Tempe, Arizona and now, Commerce City. In recent years, she has experienced a varying intensity of asthma symptoms, based on where she resides.

Geda is a first-generation American, her parents being from Ethiopia. Although she grew up a bit differently than many other Americans, she says she is grateful for the experience her family provided her. On the contrary, she is not grateful for her health issues.

“In Denver, it was worse than when I lived with my parents in Thornton,” Geda said, speaking of her asthma.

Geda recalled not needing to use her inhaler as much in Arizona. She felt her asthma was more controlled at that time. Now she notices that her inhaler use has gone up in frequency.

A major difference between Commerce City and other places in Colorado is the presence of Suncor Refinery. The immense and industrial-looking facility is hard to miss while driving through town. It is a tangle of pipes, stacks, tanks and other industrial equipment. Oftentimes, the site is accompanied by the smell of rotten eggs. It supplies fuel and petroleum to people across Colorado.

Geda noticed that she is in need of her inhaler more often living in Commerce City than any other location. Her estimation of use is about six times per day. She notes that normal inhaler use is about two-four times per day.

“I feel like when I'm home, like I use it way more than when I'm on vacation and stuff,” Geda said.

Geda uses an array of asthma medications. Most notably she uses Albuterol every day on a need-be basis, the medication is generally used three to four times per day. Secondly, Geda also takes Symbicort, a steroid inhaler in the morning and night, which is supposed to calm the airways down directly and thereby prevent attacks. Finally, she takes Prednisone, a systemic steroid that also helps reduce lung inflammation. Geda also has a nebulizer, which is a device that can turn liquid asthma medicine into a mist.

Geda has visited the doctor four times since living in Commerce City, two visits being to the emergency room.

“When I would take a breath, my lungs just wouldn't expand,” Geda said while recalling her ER visits. “My inhaler wouldn't be working, nothing was helping.”

Geda's Albuterol inhaler, which she brought to her gymnastics coaching job on April 4, 2024

Geda's Albuterol inhaler, which she brought to her gymnastics coaching job on April 4, 2024

Pollution and health risks in Commerce City

Ozone pollution is known to exacerbate asthma and also cause a variety of other health impacts.

Ozone is a type of gas which occurs naturally in Earth’s atmosphere but also through man-made means. There are two types of ozone: ground-level (tropospheric) and stratospheric (the upper-atmosphere). Ground-level ozone is the type that causes concern.

Those who breathe in ground-level ozone can experience many adverse health effects. Some respiratory symptoms include coughing, chest tightening, shortness of breath, throat irritation and more. On the more serious side, ozone concentrations are associated with increased asthma attacks and hospital admissions.

Commerce City’s website cites ground-level ozone as a key air quality concern for the community.

“The common ones are nosebleeds, headaches, migraines,” Guadalupe Solis, the director of environmental justice programs at Cultivando, an organization in Colorado, said. “At any given time, a community member isn't just breathing in one chemical, but a variety and a toxic mixture of all types of chemicals, so there's cumulative impact. It can cause things like exacerbating individuals who already have asthma and sending them to the emergency room.”

These kinds of impacts are well known to Lucy Molina and her children, who live near Suncor. Molina, who identifies as Latina, says many of her family members are battling health issues, including asthma and even cancer. At first, she thought it might be a case of “brujería,” or witchcraft. But then she learned more about the air quality issues in her neighborhood. And now she fears that they will cause her to die prematurely. “That’s what these illnesses cause,” she said.

“I value my kids enough to be here today to protect their future,” Molina said after the press conference held by an environmental law organization called Earthjustice held at the Colorado State Capitol in February 2024. At the conference, three bills meant to control Colorado’s ozone pollution were rolled out. “All of our childhood, we have not been valued by our own government because of what we look like. That's environmental racism. And that is really what we fight against.”

Community members often come to Cultivando with concerns.

“The community was coming to us and saying that this was impacting their health,” said Cultivando’s Guadalupe Solis. “They have told us things like, ‘My kids are having nosebleeds, nausea, headaches and migraines to the point where they can't study.’”

Another concern in Commerce City is the water quality. In 2022, Earthjustice and Westwater Hydrology LLC released a report detailing Suncor’s discharges of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS/PFOS. The findings from a 2021 sampling showed that Suncor was releasing a great amount of PFAS/PFOS chemicals into Sand Creek, located in Commerce City.

PFAS/PFOS are often referred to as ‘forever chemicals,’ because they can last for thousands of years. PFAS/PFOS pose potential human health and environment risks such as effects on reproduction, growth and development, the immune system and more according to the CDC.

Based on the report from Earthjustice, the Colorado Sun wrote that Suncor released a spike in PFAS/PFOS substances in June 2023, totaling 2,500 parts per trillion. The EPA’s 2022 health advisory is 0.02 ppt. In other words, Suncor’s emission of the toxic compounds was 125,000 times over the legally allowed limit.

The report found that 47% of PFAS chemicals in Sand Creek, which runs through Commerce City, could be attributed to a Suncor water outfall known as Outfall 020A. Substances and water from Suncor are drained through this outfall. It was further determined that 18% of the total PFAS mass found in South Platte River was contributed to by Outfall 020A.

The South Platte River flows into Sand Creek. The water source provides drinking water and irrigation uses to many areas in the Front Range.

“A big issue in Commerce City is the water quality,” an anonymous Suncor employee and Commerce City resident said. “In our home we had to buy water softener, but it did still not make much of a difference. Having to take these extra steps made our water bill very high.” The source wishes to stay undisclosed as they do not want to risk their job position at Suncor.

Water and air pollution go hand-in-hand, according to Mary Reiley, a retired Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) worker.

“Water is one of those things where it all runs downhill and it carries with it anything that comes into it,” Reiley said. “Whether it's air pollution, superfund sites, soil issues, land use or anything like that – it all impacts water.”

In March 2023, CDPHE released a statement saying that a new water permit was published to Suncor that limits the release of PFAS/PFOS into Sand Creek.

Federal and state regulations are established to control pollution.

The Clean Air Act is a federal law which regulates air emissions from both stationary and mobile sources. It requires the EPA to establish National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Part of the Clean Air Act identifies primary and secondary air quality standards. Primary standards provide public health protection. This includes the protection of asthmatics, children and the elderly. Secondary standards provide public welfare protection. Part of secondary standards includes protection against damage to animals, crops and buildings.

Pollutants listed in the National Ambient Air Quality Standards table include carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide and ozone.

Suncor was fined by the EPA in 2023 for exceeding emission limits of a particularly dangerous volatile organic compound, or VOC called benzene.

VOCs are gases emitted from products or processes. Short term effects include headaches, dizziness, drowsiness and more. Long term effects are correlated with increases in rates of leukemia, harmful reproductive effects in women and more.

Most alarmingly, benzene is a known carcinogen, according to the CDC. Carcinogens are agents that can cause cancer, as determined by The International Agency for Cancer Research and the EPA.

These harmful pollutants often disproportionately impact people of color. This is environmental racism. Environmental justice is a term used when expressing ways to remedy the issue.

Colorado is no stranger to environmental justice.

The Colorado Environmental Justice Act was approved by Gov. Jared Polis in 2021. As a course of action, the bill explains that the state will create an environmental justice task force to address environmental justice inequities and other issues. Other paths of action including the requirement of greenhouse gases in the list of air pollutants required to be reported, are listed in the bill.

Lucy Molina poses for a portrait at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Lucy Molina poses for a portrait at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Environmental justice and local activism

Renee Chacon during a speech at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Renee Chacon during a speech at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Colorful Colorado is a state with illustrious lakes, magnificent mountains, diverse wildlife, and over 300 days of sunshine a year. With its beautiful scenery, it may not be the first place that comes to mind when one considers redlining, pollution and environmental racism.

A site called Colorado Enviroscreen tracks pollution levels in different parts of Colorado. It generates a score from 0-100, the higher the score means the population in that area faces a greater environmental burden. Commerce City, with a majority non-white population, has a score of 89. In comparison, Boulder, a nearby college town with a majority white population, has a score of 61.

Boulder’s population was 78.3% White (Non Hispanic) in 2021. In contrast, Commerce City had a White (Non Hispanic) population of 41.8%.

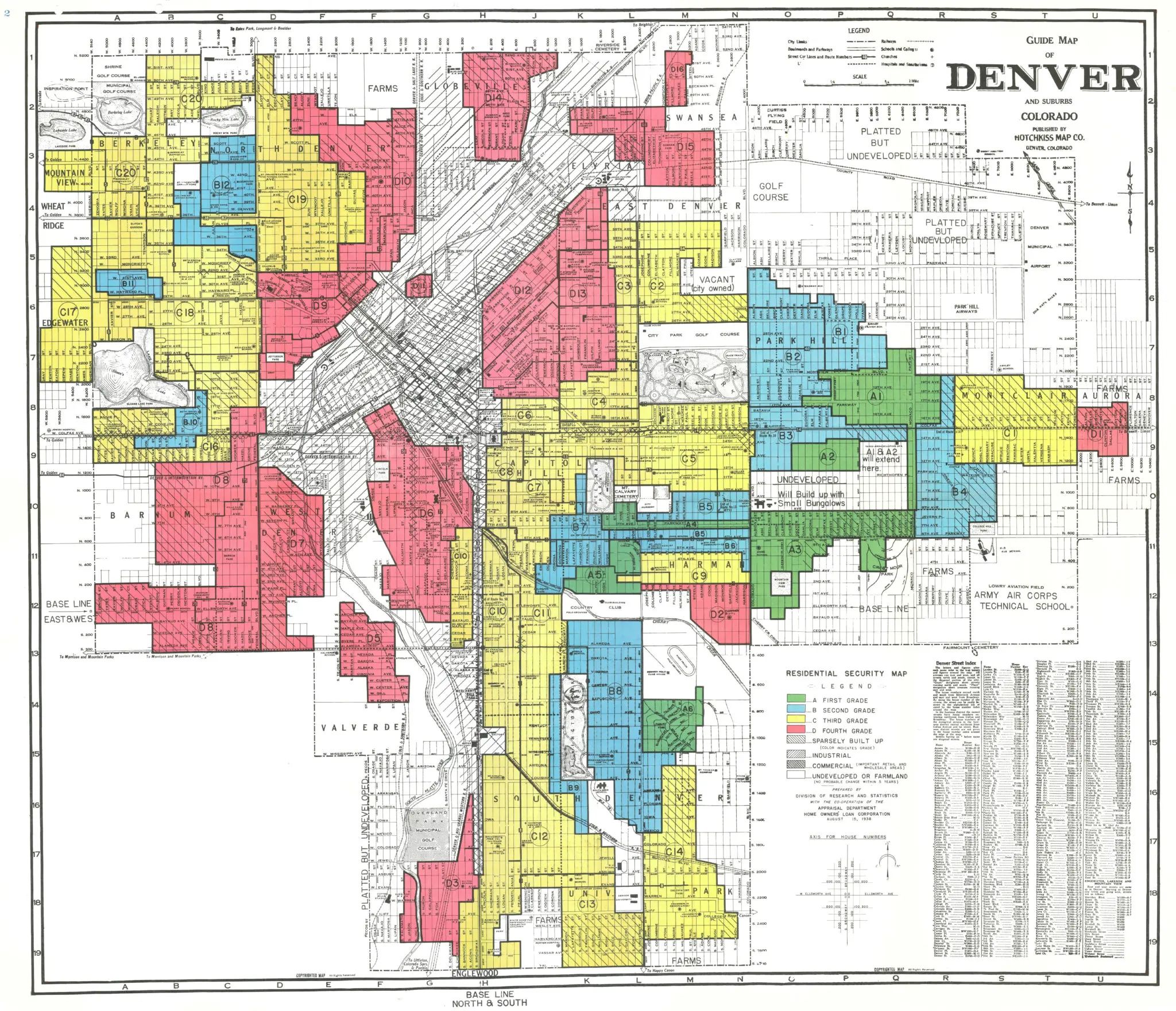

This higher environmental burden on people of color can be partially attributed to the practice of redlining, which historically furthered segregation based on skin color.

The history of redlining in The United States is deep-rooted, Colorado being no exception. It is a discriminatory practice which denies certain financial services, such as mortgages and insurance loans to residents of certain areas based on race or ethnicity. In the 1920s and 1930s, government-issued mortgages were established for homeowners. On redlined maps, neighborhoods marked red were deemed unworthy of participating in homeownership programs. Most of the red neighborhoods contained primarily Black residents. As a result, these residents were denied government-insured loans. Since Black residents were unable to participate in the same housing programs as many White people, they were unable to get homes in certain neighborhoods and segregation extended.

During Earthjustice’s ozone bill press conference at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024, community members and group representatives joined legislators at the state capitol building to roll out three bills addressing the ozone crisis.

The Colorado State Capitol building on Feb. 22, 2024

The Colorado State Capitol building on Feb. 22, 2024

“Let's not forget it was illegal for black or brown people to buy or rent in many areas in Colorado or the seller or lessor would be jailed,” Rashad Younger, the second vice president for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP, representing Wyoming, Colorado and Montana said during the press conference. “As a result of this discrimination, our communities are far more likely to live near sources that create ozone and other air pollution.”

According to Nikita Habermehl, a physician who works in the emergency department at Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, CO, communities close to Suncor have a higher risk of developing respiratory diseases such as asthma exacerbations. This tracks as there is a higher amount of ozone pollution, known to worsen asthma symptoms, in Commerce City, compared to other areas in Colorado.

“We've seen a dramatic difference from those communities,” Habermehl said.

Redlining correlates with environmental racism and environmental injustices and, in many cases, it has resulted in large numbers of people of color living in unhealthy environments, such as Commerce City.

1934 redlining map via Mapping Inequality

1934 redlining map via Mapping Inequality

Bringing environmental justice to communities is not a black and white issue, according to retired EPA worker, Mary Reiley. She said the EPA’s website uses the term “environmental justice” rather than “environmental racism” because the issue also has to do with economics.

Reiley said living near an oil refinery is less desirable than in other areas. This makes housing cheaper. This results in people of lesser means winding up in areas with more pollution.

There were three ozone bills introduced at the February 2024 Earthjustice press conference.The first bill addresses improving pollution reduction measures. The second one modifies the process to obtain permits for activities that affect air quality, and the third bill increases the enforcement of violations by strengthening air quality regulations and holding polluters, such as Suncor, accountable.

Cultivando is a major player in the long-fight for environmental justice. The group partially represents the Latinx Community in Adams County. They monitored the refinery’s pollution levels from 2020-2023.

“We made the decision to stop the monitoring because we had successfully completed the requirements of the SEP (Simplified Employee Pension Plan) and we had the data and the evidence needed,” Cultivando’s Guadalupe Solis said. “This air monitoring project was really to validate what our communities were already experiencing and saying.”

Cultivando worked with Boulder A.I.R. to conduct air monitoring up until June of 2023. Results showed that Denver and areas in Northern Colorado, near the front range, repeatedly failed to meet EPA air quality regulations when it came to ozone pollution.

In addition to Solis, many other community members attended the event. Speakers included a senator, representatives, a reverend and more.

“Honestly, Suncor has been a bad actor for so long that they've been in non-compliance,” Renee Chacon, Commerce City council member said. “It has taken two lawsuits and settlements, and they still are not up to even updating their operations and systems.”

Chacon is also a co-founder of Womxn from the Mountain, an Indigenous non-profit.

Chacon comes from the west side of Denver, and says she has personally experienced negative health effects as a result of poor water quality.

Chacon suffers from Immune Thrombocytopenia, also known as ITP. She believes that the disorder correlates with the polluted water, although the cause of it is still unknown. One study found that prenatal exposure to air pollution is correlated with having it. ITP results in bleeding, which is hard to stop.

“If I get too stressed out, my white blood cells eat my platelets and I clot,” Chacon said. “I’ve been hospitalized on a number of occasions where I have absolutely no platelets.

Getting these bills passed may not solve all the problems in Commerce City, but it is a good place to start.

“I feel like that state is finally learning what it means to be an ally, but cannot call itself an ally yet,” Chacon said. “In all honesty, when it comes to the regulatory process, they’ve kind of been cowardly protecting those communities.”

Suncor Refinery’s tumultuous past

Commerce City on March 10, 2024

Commerce City on March 10, 2024

In Feb. 2024, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment announced that Suncor is being hit with a $10.5 million penalty after releasing toxic chemicals into the air for years, and it’s not the first time Suncor has been penalized.

In 2023, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), along with the CDPHE, released a report analyzing the frequency of air pollution incidents at Suncor. They found that during the period of 2016-2020, “Suncor had the greatest number of tail gas incidents that caused releases of excess sulfur dioxide.”

According to Law Insider, Tail gases are “gases and vapors released into the atmosphere from an industrial process after all reaction and treatment has taken place.”

“Historically, the oil and gas refinery has been around since the early 1900s,” Solis said. “It was taken over by Suncor in the early 2000s, so our community is experiencing a variety of different health impacts from breathing in this toxic air.”

A fact-sheet, made in part by Cultivando, says that Suncor releases the following air pollutants annually:

- 886,000 tons of carbon dioxide, or CO2; according to the Food and Safety Drug Administration, CO2 inhalation can cause headaches, drowsiness, rapid breathing and more.

- 24 tons sulfur dioxide; this gaseous air pollutant, as found in the 2023 EPA report, can cause respiratory symptoms, increased ER visits, shortness of breath and other issues, according to the American Lung Association.

- 12.5 tons of hydrogen sulfide; the CDC states that hydrogen sulfide gas has a strong odor of rotten eggs. It may cause eye irritation, coma, convulsions and more.

- 25 tons of ozone-forming VOCs; an academic journal article states that ozone exposure is associated with increased mortality due to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

- 4 tons carbon monoxide; The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, known as OSHA says the gas can cause chest tightening, dizziness, nausea and more.

- 49 tons nitrogen oxide; this gas can aggravate respiratory diseases, such as asthma, according to the EPA.

- 55 tons particulates; according to the EPA, particulate matter is small particles that can get into your lungs and bloodstream. This can aggravate asthma, irregulate one’s heartbeat, cause premature death in those with lung and/or heart disease and cause an array of other issues.

In a press release, the CDPHE stated that they are requiring Suncor to take steps toward preventing future violations. Some of the money will be given to the state’s Environmental Justice Grant Program, which helps disproportionately impacted communities that experience pollution.

The penalty is similar to a 2019-2020 settlement, also issued by the department. It totalled $9 million for air pollution violations.

In an email, David Cobb, the EPA region eight section chief shared that the EPA has recently issued several enforcement actions toward Suncor after their violations of the Clean Air Act.

For example, in August of 2023, Suncor and the EPA reached a settlement of $300,030 after they were found to be improperly preventing accidental releases of chemicals and not fulfilling toxic chemical release reporting requirements. In the same month, the EPA objected to Suncor receiving an air permit.

In September of 2023, the EPA reached a settlement with Suncor after the company was found to be producing non compliant fuel that exceeded benzene and VOC limiting requirements. This resulted in excess amounts of hazardous air pollution. In this case, Suncor was fined a civil penalty of $160,660 and required to implement an environmental protection project costing $600,000.

Cobb said the “EPA doesn’t offer ‘personal’ opinions,” when asked for his thoughts on Suncor’s violations.

“It's, like, a known thing that it's not good, that Suncor is not good,” Geda said. “Maybe let's not kill the Earth around us.”

In addition to violating the Clean Air Act and committing pollution violations, Suncor has allegedly committed labor violations in the past.

In 2009, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration put out a news release regarding a serious citation of Suncor’s Commerce City location. They found that the refinery was not properly managing safety operations while processing hazardous chemicals and other procedures. Serious citations are issued when death or serious physical harm is likely to result from a violation.

OSHA proposed penalizing Suncor violations totalling $81,000 and one willful violation with a proposed penalty of $49,500.

“I had to work seven 12 hour shifts a few months in a row but that wasn’t the only time I had to do that,” the anonymous Suncor employee said in text communication. “Over Covid I had to do it as well.”

Builder Developer News reported that workers are transported to their worksite in a bus, which essentially strands them there for many hours. Additionally, the article’s source noted that employees are not allowed to bring phones into the worksite, to prevent capturing what goes on in the facility.

“I didn’t only spend all of my day at the job but I had to sacrifice many parts of my life. Family events or parties I could only attend very little,” the anonymous Suncor employee said in text communication. “Schedules truly change week to week not giving employees consistency.”

The Suncor employee also said there is no sick pay system set in place. The employee stated they are unable to use hours accrued for sick days, or days that they are simply unable to make it into work.

Suncor Refinery on March 9, 2024

Suncor Refinery on March 9, 2024

Underneath the train tracks leading into Suncor Refinery on March 9, 2024

Underneath the train tracks leading into Suncor Refinery on March 9, 2024

Overpass in Commerce City, Suncor Refinery shown in the background on March 9, 2024

Overpass in Commerce City, Suncor Refinery shown in the background on March 9, 2024

Commerce City is a single case of environmental injustice, amongst many

The broad concept of environmental racism is not a new one, and it certainly is not unique to Colorado.

In 2014, a well-known example of environmental racism took place in Flint, Michigan. At the time, residents of Flint had their drinking water switched from Lake Huron’s water supply to that of the Flint River. The water, not properly treated, became contaminated with lead.

In April of 2015, it was reported that Flint, Michigan, had a population of 55.1% African Americans.

Brittany Greeson, a Flint Journal photojournalism intern in 2015, lived through the water crisis.

“You had all these people whose concerns were being voiced over and over again. It really seemed like no one was listening to them,” Greeson said. “I could even tell my water was bad.”

According to Greeson, when she was reporting in Spring of 2015 residents were claiming something was wrong with their water. It was not until she left for the summer and returned midway through the fall that their claims were validated by experts.

For months, citizens of Flint were drinking lead-contaminated water, and no one did a thing about it.

Upon her return, Greeson reported needing to use bottled water for consumption and self showering. When she did use Flint’s water supply, she noticed it had a blue tint to it, and compared it to swimming pool water. She also noticed patches of dry skin appearing on her body.

“I think Flint is a story of how our democracy has failed us. Sometimes I want a politician to look me square in the eye when I ask them the question: ‘So you're telling me that if I'm born into a certain zip code, that it's okay for me to have a completely different quality of life and life expectancy? And you think that's democracy?’ That's not democracy,” Greeson said. “It's just been really infuriating that it's 2024 and here you're born and who you're born to is going to literally determine your health and your wellbeing.”

Learning from past events, such as Flint can help society prevent itself from repeating the same mistakes in present circumstances.

Back in Colorado, Suncor is not the only contributor to poor environmental conditions. Old Superfund sites, including Sand Creek and Rocky Mountain Arsenal are other areas of concern.

Superfund is an EPA-run program that cleans up some of the most contaminated pieces of land in the nation. These sites are added to a National Priorities List, when they are determined to be polluted or in need of further investigation.

The Sand Creek site was the location of many businesses including an oil refinery, a pesticide manufacturing facility, an herbicide chemical plant and a landfill. Operations led to contaminated soil, air, groundwater etc. It has since been cleaned up, but the EPA website states that there is insufficient data to determine whether human exposure to contaminants is under control.

Production of incendiary munitions and chemical warfare agents for the military took place at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal between the early 1940s and early 1980s. An example is the creation of dichlorodiethyl sulfide, commonly known as mustard gas. Later on, pesticides were produced at the site. As a result, on their website, the EPA said that health risks came from “ingesting or touching contaminated soil, surface water or groundwater.”

Although Sand Creek and Rocky Mountain Arsenal are now deemed safe by the EPA, the cleanup is not fool-proof, according to an article from National Geographic. It is hard to determine the effects on people actually living in and around these areas, even post-cleanup.

Sand Creek on March 10, 2024

Sand Creek on March 10, 2024

Biker's ride through Sand Creek on March 10, 2024

Biker's ride through Sand Creek on March 10, 2024

Ducks walk down a path at Rocky Mountain Arsenal on March 10, 2024

Ducks walk down a path at Rocky Mountain Arsenal on March 10, 2024

Animals at Rocky Mountain Arsenal on March 10, 2024

Animals at Rocky Mountain Arsenal on March 10, 2024

Entrance to Rocky Mountain Arsenal on March 10, 2024

Entrance to Rocky Mountain Arsenal on March 10, 2024

Denver’s larger environmental justice issues and solutions

“It can be very disheartening,” Solis said. “Also, I think that with the help of these amazing legislators and all these key stakeholders, I think that there's a big window and a big momentum in the right direction to finally get the actions and the regulations that we need to protect our communities.”

On April 22, 2024 (Earth Day), Cultivando will share their findings regarding toxic air exposure in Commerce City.

When asked in an email about EPA’s future plans for Suncor monitoring, Cobb said they will continue their efforts. Part of these efforts will include working with organizations like Cultivando and listening to community members.

Following the email request for an update on Suncor’s $10.5 million penalty, the Colorado Air Pollution Control Division said the petroleum refinery has already paid fines to CDPHE and the EPA. They have until Dec. 31, 2026 to put the remaining $8 million of the settlement into ‘power reliability projects’.

In an email, Cobb shared that the EPA plans to continue monitoring Suncor’s compliance with requirements and industry standards. The EPA will also continue ‘robust community engagement’ as a way to ensure concerns are raised and transparency is maintained.

Guadalupe Solis at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Guadalupe Solis at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Renee Chacon at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Renee Chacon at the Colorado State Capitol on Feb. 22, 2024

Since EPA’s inception, a slew of hazardous waste sites across the country have been cleaned up. Colorado sites include Rocky Flats, Rocky Mountain Arsenal, Sand Creek and more.

“What EPA has done, and the citizens and legislatures that made EPA happen – we are in such a better place than we were, you know, 40 years ago,” Reiley said. “ People talk about layers of an onion. And you keep peeling things back.”

They are not the only one’s peeling back layers on the issue.

In recent research from The University of Colorado Boulder, grad student Alexander Bradley used satellite imagery to show greater pollution in redlined communities of Denver, such as Commerce City.

Reiley, who primarily focused on water pollution issues at the EPA for 36 years, shared her thoughts on coming to a potential solution. She feels that solving the problem requires experts from a variety of disciplines, including ecologists, chemists, lawyers and more.

“As I call them, you got to get all the ‘ologists’ together.” Reiley said. “You can't solve this by just taking on one component, it has to be done in a very transparent and collaborative approach with the community that lives there.”

Photo provided by Mary Reiley, pictured is her doing EPA work in 1990.

Photo provided by Mary Reiley, pictured is her doing EPA work in 1990.

Photo provided Mary Reiley, pictured is her working for the EPA in 1990.

Photo provided Mary Reiley, pictured is her working for the EPA in 1990.

Photo provided by Mary Reiley, pictured is her working for the EPA in 2019.

Photo provided by Mary Reiley, pictured is her working for the EPA in 2019.

So, are there any upsides to living in Commerce City? According to Geda, her rent is cheap and there isn’t much traffic. But it doesn't seem to make up for the area's poor air quality, high frequency of trains running through it and long commute times to basic stores, such as Target.

“I’m going to move,” Geda said. “Probably back to Denver.”

With Suncor’s fines being reported on, and University of Colorado researchers looking into environmental injustices, one can hope that enough attention is being drawn to the issue for change to be fostered.

“Environmental racism exists at all levels of government. This is embedded within our government, from the local level to the federal level,” Commerce City resident Lucy Molina said. “Through empathy, through sharing our stories we can bring justice, environmental justice.”